Social Conflict, American Style

Fake news—news articles that are intentionally and verifiably false designed to manipulate people’s perceptions of reality—has been used to influence politics and promote advertising. But it has also become a method to stir up and intensify social conflict. Stories that are untrue and that intentionally mislead readers have caused growing mistrust among American people. In some cases, this mistrust results in incivility, protest over imaginary events, or violence. This unravels the fabric of American life, turning neighbor against neighbor. Why would anyone do this? People, organizations, and governments—foreign governments and even our own—use fake news for two different reasons. First, they intensify social conflict to undermine people’s faith in the democratic process and people’s ability to work together [1]. Second, they distract people from important issues so that these issues remain unresolved. This section explores how fake news is used for distraction and intensifying conflict.

PizzagateIn one infamous case, a fake news story (and the comments people attached to it) moved one man to shoot up a pizzeria that was linked by bogus statements to human trafficking and a presidential candidate. In the incident nicknamed “Pizzagate," a man with a semi-automatic rifle walked into a regular Washington, DC pizza joint - Comet Ping Pong - and fired shots. Why? He was convinced that the pizzeria contained a hidden pedophilia trafficking ring led by Hillary Clinton and her presidential campaign. Where did he come up with this notion? Alt-right communities first created this piece of fiction, and fake news websites promoted the lie by citing specific locations such Comet Ping Pong. It was then tweeted further by people in the Czech Republic, Cyprus, and Vietnam, as well as many bots, getting the story much additional attention. Fake news - political in nature - influenced a man to fire shots inside this restaurant, nearly killing innocent people. The spread of information that was knowingly false had potentially deadly consequences [2]. |

|

Intensifying Social Conflict

People with malicious intent can use fake news to make American national conflicts more intense. Politically motivated fake news came from multiple sources: foreign governments, such as the Russian Internet Research Agency; American political operatives who used illegitimately-acquired Facebook data from the Cambridge Analytica firm to convince social media users how to vote; and from politically motivated groups, such as the alt-right, alt-left, and conspiracy theorists. Despite their different goals, they spread similar fake news stories.

Russia’s Internet Research Agency

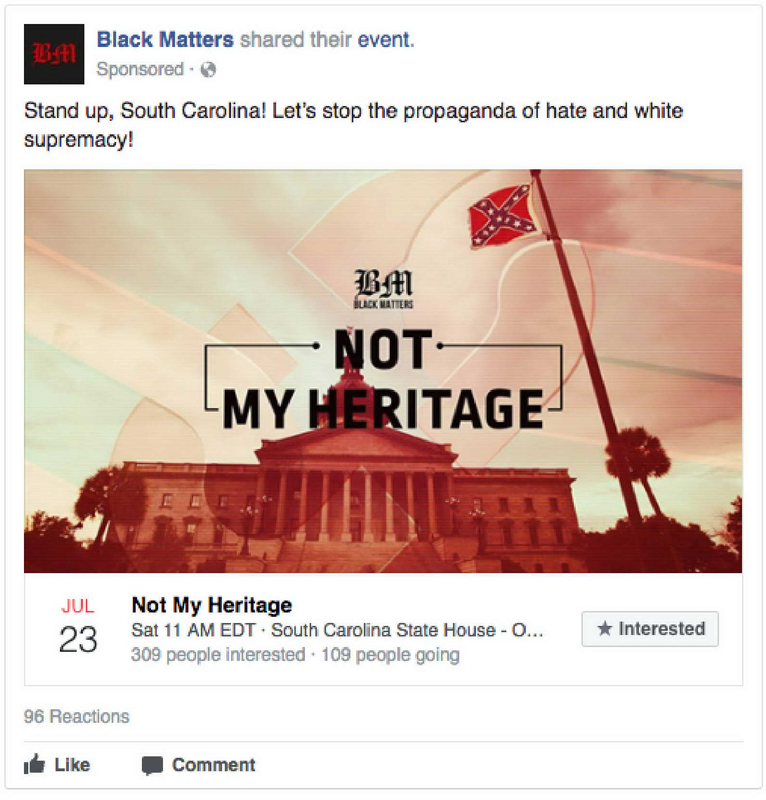

During and after the 2016 election, Russian agents created social media accounts to spread fake news that stirred protests and favored presidential candidate Donald Trump while discrediting candidate Hillary Clinton and her associates. They paid Facebook for advertisements that appeared on that site to spread fake news and turn Americans against one another. The U.S. Congressional Intelligence committees responsible for investigating fake news have released 3,500 of these advertisements to the public.

Ads focused on controversial social issues such as race, the Black Lives Matter movement, the 2nd Amendment, immigration, and other issues. The Russians even went so far as to stage protests and counter protests about a given issue, literally having Americans fight one another.

This Russian ad was targeted to people living in South Carolina on June 30, 2016. There’s no real “Black Matters” group.

Russians also paid Facebook to have this ad shown to people residing in Washington, DC:

Cambridge Analytica

“Alexander Nix, Cambridge Analytica chief, is among the executives coming under pressure for the group's business practices.” Source: Financial Times

Cambridge Analytica was a company that specialized in using data from social media to build psychological profiles about social media users in various countries. It acquired data for 87 million Facebook users without the users’ knowledge or consent [3]. With these data—specifically a person’s “Likes”—they were able to predict people’s political preferences and issue interests. Political campaign operatives coordinated by Donald Trump’s chief strategist, Steve Bannon, used this information to target political advertisements and memes on Facebook that mainly focused on discrediting Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign and influencing Americans on a number of pro-Trump issues [4]. These messages were often inflammatory, sensationalistic, sometimes violent, and false. They exploited data that many Americans never agreed to share with advertisers.

(We also talk about Cambridge Analytica when we discuss Microtargeting.)

Other Political Groups

Another major effort to disrupt American society has been to fuel fires of suspicion and conspiracy in the wake of major social tragedies—mass shootings, in particular. Conspiracy theorists were fed, and quickly reposted content that originated from Russian agents, political campaign operatives, and other fake news sources, which claimed that these shootings were staged (usually, they claimed, to fool people into supporting gun restrictions). People shared these messages across their social networks. Professor Kate Starbird at the University of Washington assessed this ripple effect by analyzing the links from tweets to websites and comments that promoted the belief that the mass shootings weren’t real [5]. Her computer program collected tweets with hashtags that included terms like “false flag,” “crisis actor,” and “staged.” Overall, she collected 99,474 tweets from 15,150 users. The tweets referenced 117 websites, 80 of which were “alternative media,” or fake news. Additionally, 44 websites had a clear political agenda: 22 were alt-right, 4 were alt-left, and 7 were anti-globalist.

Fake news poses a serious threat to American democracy. During the 2016 US presidential election, fake news was more prevalent on social media than genuine news and it’s unclear whether interventions from Facebook and Twitter and the U.S. government changed this in subsequent elections. Although social media companies are attempting to slow the spread of misinformation by implementing fact-checking programs, these tactics to identify, flag, and remove misinformation, especially regarding the COVID-19 vaccines, are not as effective as they should be. This places additional responsibility on social media users to recognize Fake News and report these posts or avoid interacting with them altogether [6]. Over 62% of Americans receive their news from social media [7]. This makes a large portion of the public vulnerable, because people who read fake news are very likely to believe it. Regardless who posts it, fake news intentionally undermines trust in the news and the government.

Fake News and the 2020 Black Lives Matter Protests

In the summer of 2020, George Floyd’s death sparked outrage in America and led to thousands of Black Lives Matter protests across the country. With BLM a leading topic across mainstream media, the prevalence of fake news on social media led to increased racial and political divides in the U.S. Misinformation, fake news articles, and falsely edited images began circulating online about BLM. Graham Brookie, director of the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensic Research Lab, explained that “The combination of evolving events, sustained attention and, most of all, deep existing divisions make this moment a perfect storm for disinformation” [8].

This article was shared across social media platforms for weeks before fact-checking sites debunked its claims. Now, it has been taken down and archived, but it reached millions of people before being proven false.

A Facebook user took an image posted by the Toronto Raptors showing their support for BLM on their travel bus, and made a false claim that the Black Lives Matter organization used donations to purchase luxury buses for themselves.

The fake news surrounding BLM negatively impacted the organization itself and even increased prejudice and racism towards African Americans: A 2022 study examined the effect of the portrayals of the BLM movement in fake news on people’s attitudes toward African Americans. People exposed to fake news about BLM reported more negative attitudes toward Black people than those exposed to accurate news sources [9]. This study it highlights the impact that fake news can have on peoples’ perceptions of Black people in America.

To combat fake news, Black Lives Matter dedicated a tab on their website titled Help Us Fight Disinformation, to report suspicious sites and stories that people see online.

Fake News and Social Conflict Abroad

Americans aren’t the only people with a fake news problem. Although Indian police have made some successful efforts to stem the sharing and influence of fake news, the picture is more tragic in Myanmar, where the government appears to ignore or encourage it:

“Facebook has become a breeding ground for pernicious posts about the Rohingya (minority ethnic group). ‘In particular, the ones that seem most problematic are government channels that have put a lot of propaganda out there, saying everything from the Rohingya are burning their own villages, to showing bodies of soldiers who may be from other conflicts but saying this is the result of a Rohingya attack’.” [10]

In another case where a government sends fake news to its own citizens, the effort is to stifle conflict rather than arouse it. Many Chinese citizens believe their government has employed as many as 2 million people to spread propaganda on social media and governmental websites [11]. The people are collectively referred to as the 50c Party because they are rumored to receive 50 cents for fake social media posts they make. Researchers have studied the 50c Party using leaked governmental emails containing 43,000 of their posts. They found that 50c Party employees generated about 448 million posts per year. However, the 50c Party isn’t aggressive towards foreign governments or Chinese citizens: Its posts praise the Chinese government or Chinese culture in an attempt to create a positive image among Chinese people toward their own government. These posts can be classified as fake news, because the 50c Party misdirects Chinese citizens and masquerades as everyday social media users when they are actually government employees.

Why would a government invest so much money to create fake news? First, when a person hears a statement from multiple people, they are more likely to believe that statement. By hiring many members of the 50c Party and having them post positive messages about China’s political landscape, the Chinese government can convince its citizens to be happy with its performance. Second, the when a bunch of posts about one topic are released at once, the topic is likely to become more popular or “go viral.” This is why the Chinese government does not have the 50c Party post steadily throughout the year. Instead, they post in bursts so that their posts are more likely to become popular. Third, the Chinese government does not release bursts of 50c Party posts at random. Instead, they wait for times when citizens are most likely to be unhappy or to protest.

Fake News and the 2022 Ukraine & Russia Conflict

The Russian invasion into Ukraine has been classified as World War Wired as thousands of Russians and Ukrainians utilize social media platforms to document the battles. While most of the social media accounts are real people, there is widespread concern about the amount of misinformation across social networking sites.

NewsGuard’s Misinformation Monitor, a fact-checking bulletin, reported an investigation in March 2022: Within 40 minutes of joining the TikTok app, accounts were shown misleading content about the war in Ukraine. These claims were both pro-Russian and pro-Ukranian, but were all false.

NewsGuard’s Misinformation Monitor, a fact-checking bulletin, reported an investigation in March 2022: Within 40 minutes of joining the TikTok app, accounts were shown misleading content about the war in Ukraine. These claims were both pro-Russian and pro-Ukranian, but were all false.

At the time of this writing the war in Ukraine is ongoing. Fake news continues to run rampant across social media platforms, and Russian and Ukrainian citizens are being asked to determine what is real and fake news as major social media platforms fail to take down a vast majority of misinformation [12].

Some Take-Aways

This section demonstrated how fake news can intensify conflict and suppress conversation about social issues. American conspiracy theorists with varying political motives post on social media intending to intensify ongoing national conflicts. Other governments use fake social media posts to keep citizens happy and distract them from important social issues. While motivations for using fake news may vary, fake news consistently undermines citizens’ ability to participate in the governance of their country and make important decisions regarding the fate of their nation.

References

[1] Office of the Director of National Intelligence, “Assessing Russian Activities and Intentions in Recent US Elections,” Jan. 06, 2017. https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/ICA_2017_01.pdf (accessed Aug. 03, 2018).

[2] M. Fisher, J. W. Cox, and P. Hermann, “Pizzagate: From Rumor, to Hashtag, to Gunfire in D.C.,” Washington Post, Dec. 06, 2018. https://www.washingtonpost.com/local/pizzagate-from-rumor-to-hashtag-to-gunfire-in-dc/2016/12/06/4c7def50-bbd4-11e6-94ac-3d324840106c_story.html (accessed Aug. 03, 2018).

[3] I. Lapowsky, “Facebook Exposed 87 Million Users to Cambridge Analytica,” Wired, Apr. 04, 2018. https://www.wired.com/story/facebook-exposed-87-million-users-to-cambridge-analytica/ (accessed Aug. 03, 2018).

[4] M. Rosenberg, N. Confessore, and C. Cadwalladr, “How Trump Consultants Exploited the Facebook Data of Millions,” The New York Times, Apr. 02, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/03/17/us/politics/cambridge-analytica-trump-campaign.html (accessed Aug. 03, 2018).

[5] K. Starbird, “Examining the Alternative Media Ecosystem through the Production of Alternative Narratives of Mass Shooting Events on Twitter,” Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media (ICWSM 2017), Montreal, Canada, May 2017, pp. 230-239. https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/article/view/14878

[6] Center for Countering Digital Hate, “The Disinformation Dozen,” Center for Countering Digital Hate | CCDH, Mar. 21, 2021. https://counterhate.com/research/the-disinformation-dozen/ (accessed Jun. 27, 2022).

[7] E. Grieco, “More Americans are Turning to Multiple Social Media Sites for News,” Pew Research Center, Nov. 02, 2017. http://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2017/11/02/more-americans-are-turning-to-multiple-social-media-sites-for-news/ (accessed Aug. 03, 2018).

[8] C. Georgacopoulos and T. Poche, “Fake News, Disinformation, and the George Floyd Protests,” Fight Fake News. https://faculty.lsu.edu/fakenews/about/protestfakenews.php (accessed Jun. 27, 2022).

[9] C. Wright, K. Gatlin, D. Acosta, and C. Taylor, “Portrayals of the Black Lives Matter Movement in Hard and Fake News and Consumer Attitudes Toward African Americans,” Howard Journal of Communications, pp. 1–23, Apr. 2022, Accessed: Jun. 28, 2022. [Online]. Available: https://doi.org/10.1080/10646175.2022.2065458

[10] The World Staff, “In Myanmar, Fake News Spread on Facebook Stokes Ethnic Violence,” The World from PRX, Nov. 01, 2017. https://theworld.org/stories/2017-11-01/myanmar-fake-news-spread-facebook-stokes-ethnic-violence (accessed Jun. 28, 2022).

[11] G. King, J. Pan, and M. E. Roberts, “How the Chinese Government Fabricates Social Media Posts for Strategic Distraction, not Engaged Argument,” American Political Science Review, vol. 111, no. 3, pp. 484–501, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000144

[12] S. Brown, “In Russia-Ukraine War, Social Media Stokes Ingenuity, Disinformation,” MIT Sloan, Apr. 06, 2022. https://mitsloan.mit.edu/ideas-made-to-matter/russia-ukraine-war-social-media-stokes-ingenuity-disinformation (accessed Jun. 28, 2022).