Accompanying the increasing amount of fake news and misinformation online, there are numerous platforms on the web for authentication, verification, or fact-checking the truthfulness of news stories. The systems themselves are very useful. The limitations in their effectiveness in helping dispel fake news seem to come from their being under-used, and the section of our website on cognitive biases explains a lot about why people don’t take advantage of fact-checking systems. Nevertheless, many efforts have in fact been made and strategies have developed to assist us in distinguishing false information from the truth.

News Agencies’ Fact-checking Reports

There are quite a number of reputable news media outlets that offer fact-check reports regularly. They can be used to monitor or verify the content of many news stories, as well as the accuracy of statements made by politicians. Some researchers suggest that simply knowing that such tools exist constrains politicians from making false claims, and pressures them to make statements more cautiously. Most fact-checking news agencies contact politicians to clarify or correct their inaccurate statements (although some politicians never directly respond) [1].

Some fact-checking outlets provide “true or false” ratings for statements made by politicians. Fact Checker, from the Washington Post, for example, indicates if a statement made by a politician is true by awarding certain symbols. Awarding “Geppetto Checkmark,” for example, suggests that a statement is true.

“One Pinocchio” means mostly true. “Two Pinocchios” indicates half true. “Three Pinocchios” means mostly false, and “Four Pinocchios” means absolutely false.

Independent Fact-Checking Resources

Other fact-checking sites are independent from traditional news media outlets, and are solely dedicated to professional fact-check services. Politifact, for example, rates statements as “True,” “Mostly True,” “Half True,” “Mostly False,” and “False.” Such sites are selective in terms of what statements to verify based on whether the statements are newsworthy and whether they’re rooted in facts that are verifiable.

Yet other fact-checking sites focus on providing additional information and context to politicians’ statements, to help readers make their own judgments about the validity of those statements. FactCheck.org does not rate politicians’ statements by true or false, but rather provides detailed evidence for or against the statements and lets you decide whether they are true or false. You can also submit inquiries directly to the site about various topics including political policies, rulings, and rumors related to other societal issues. FactCheck.org then posts answers to readers’ questions if they’re verifiable and fact-based.

Resources for Journalists, Fact Checkers, and Policy Makers

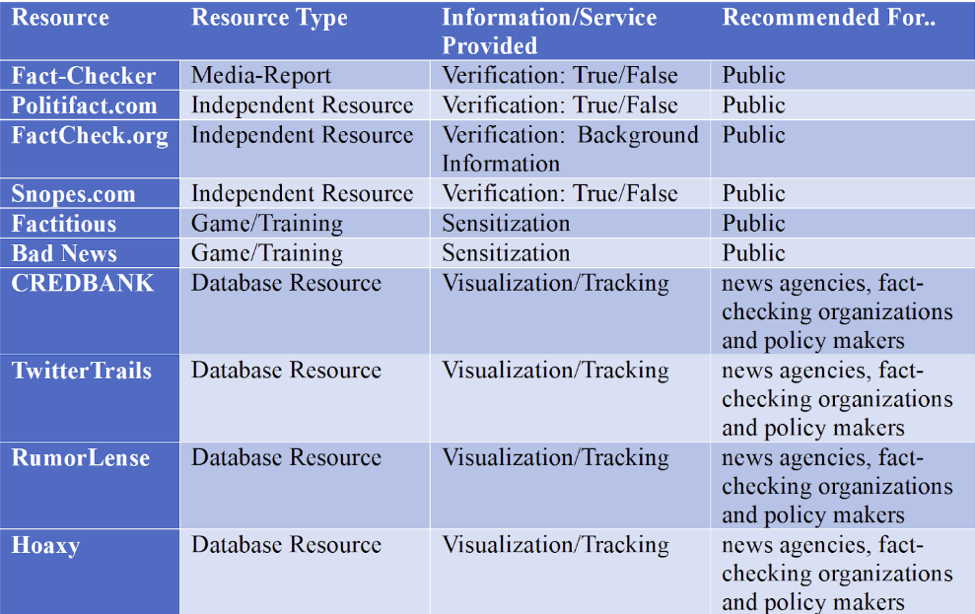

Various database resources have become available for news agencies, fact-checking organizations, and policy makers to help effectively address the spread of false information and fake news. CREDBANK, a dataset of tweets, for example, helps researchers who study misinformation by providing credibility annotations. TwitterTrails and RumorLense also help researchers visualize and track the spread of rumors online. The Hoaxy system is also well known for assisting researchers and other experts in tracking how particular misinformation and false contents spread over a social network online. The system works on the basis of the data it has been collecting since June 2016 in relation to the spread of misinformation throughout public Twitter streams.

The table, below, shows a number of major fact-checking services, how they operate, and their primary audience.

Shortcomings and Concerns

Despite the presence of a variety of professional fact-checking sites and tools, there are some inconsistencies and other shortcomings among them. The sites may not be as reliable or credible as expected, because of the lack of consistency and coherence among different fact-checking sites. For example, Fact Checker and Politifact rarely check the same statements, and even when they do check the same statements, they often don’t agree with one another on the truthfulness of what they checked [1]. This may confuse people even further and even compel people not to reconsider their preexisting perceptions of a story’s truthfulness.

When fact checks reach online media consumers, their ability to change people’s beliefs are also somewhat limited. Previous studies have shown ambiguity about the efficacy of fact-checking. While some studies point out that the political identity or general ideology of fact-checking sites lead to failures in fact-checking, others argue that debunking fake news directly changes our beliefs about whether an article is real or fake [2]–[4].

Research concerning COVID-19 information has found that fact-checking reduces misperceptions of what is real or fake news in the short term, especially among people who are most vulnerable to believing false claims surrounding the pandemic. Individuals were considered vulnerable who had distrust towards the health care system and toward mainstream media, as well as more conservative beliefs [5]. However, the researchers found that positive effects of fact-checks don’t persist over time, even after repeated exposure to content that disproved COVID-19 misinformation. Essentially, fact-checks can successfully change fake beliefs instilled by fake news temporarily, but their effects are disappointingly short-lived.

Suggestions

So when should we check for facts? We don’t expect everybody to verify everything they read. But we strongly recommend that you fact-check before you share, like, or comment on a news item, in social media. It’s important to get into a habit of fact-checking, given the cognitive biases that make us receptive to fake news. When people articulate an opinion based on something they claim is real or is a fact, it would be a good idea to check how real it is. You should question the reliability of facts even when people you know and like provided them in their own good faith. Given the diversity of resources, reports, sites, and systems available for us to verify information, it’s also important to spend enough time weighing one information source against another and develop sufficient insight that will assist you in preventing the spread of fake news in the future.

References

[1] C. Lim, “Checking How Fact-Checkers Check,” Research & Politics, vol. 5, no. 3, 2053168018786848, Jul. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168018786848

[2] H. Allcott and M. Gentzkow, “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 211–236, May 2017, https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211.

[3] N. Walter, J. Cohen, R. L. Holbert, and Y. Morag, “Fact-Checking: A Meta-Analysis of What Works and for Whom,” Political Communication, vol. 37, no. 3, pp. 350–375, May 2020, https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2019.1668894.

[4] D. Walter and Y. Ophir, “News Frame Analysis: An Inductive Mixed-Method Computational Approach,” Communication Methods and Measures, vol. 13, no. 4, pp. 248–266, Oct. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1080/19312458.2019.1639145.

[5] J. M. Carey et al., “The Ephemeral Effects of Fact-Checks on COVID-19 Misperceptions in the United States, Great Britain, and Canada,” Nature Human Behaviour, vol. 6, no. 2, Art. no. 2, Feb. 2022, https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-021-01278-3.