Why do people fall prey to fake news stories? Can't they just tell when they come across them? Having such easy access to real facts and fact checkers surely takes care of the problem, right? Unfortunately, part of the reason that fake news is such a problem is that people do fall for these stories, and being shown the facts doesn’t help correct this problem.

|

James McDaniel […] said he created a fake news website…as a joke to see just how naive Internet readers could be. UndergroundNewsReport.com was launched Feb. 21. In less than two weeks, more than 1 million people had viewed stories on the site and spread them across social media platforms. […] “I continued to write ridiculous things they just kept getting shared and I kept drawing more viewers," McDaniel told PolitiFact. "I saw how many fake ridiculous stories were making rounds in these groups and just wanted to see how ridiculous they could get." McDaniel even tried to warn viewers by putting a disclaimer on the bottom of his web pages saying his posts "are fiction, and presumably fake news." While a handful of people took the time to email him to ask if stories were real or send hate mail, most of the comments on his links blindly accepted what he wrote as the truth. (Quoted from Politifact.com) |

This isn’t a matter of gullibility. It’s due to a feature of human thinking called cognitive biases. Cognitive biases are detours or shortcuts in reasoning, remembering, or evaluating something that can lead to mistaken conclusions. They’re universal. Everyone has them.

This section explains how cognitive biases operate—what goes on inside people's heads that makes us more likely to fall for fake news, and for us to continue to believe false information even after it's been corrected.

Why do people have cognitive biases? Normally, these mental shortcuts make our lives easier. You don't need to re-learn your path from home to work or school every day, become it’s so ingrained in your mind that you can follow it without thinking. This "automatic process" allows people to conserve mental energy for things that are more complicated [1]. At the same time, cognitive biases can cause mistakes in our thinking, too. They can act as blinders, leading us not to realize something that might have been apparent. They can also make one part of our mental perspective play a disproportionate role in our thinking. A common example of this is younger people mistakenly believing they don't need health insurance because they are healthy generally [2]. This seems perfectly logical to a healthy person, but overlooks the possibility of catastrophic events.

Cognitive Biases and Fake News

Cognitive biases also affect the way we use information. Four types of cognitive biases are especially relevant in relation to fake news: First, we tend to focus on headlines and tags without reading the article they’re associated with. Second, social media’s popularity signals affect our attention to and acceptance of information. Third, fake news takes advantage of partisanship, a very strong reflex. And fourth, persistence--there’s a weird tendency for false information to stick around, even after it’s corrected.

Acting without Reading

The first of these biases is the tendency to rely on attention-getting signals sent by fake news pieces without evaluating the information accompanying these signals all that deeply. An unfortunate fact about is that many people form opinions about news articles without ever having read them [3].

A humorous, if alarming, example of this comes from a social experiment done by National Public Radio (NPR). As a joke, NPR shared a headline on their Facebook page entitled, "Why Doesn't America Read Anymore?" If users clicked the link, they were directed to a page on NPR's website explaining that the article was a joke. But many viewers, without reading the article, went right ahead and posted comments in response to the headline, clearly not having read the article [4].

Source: NPR Facebook page

This isn’t an isolated incident. Other sites also report that many comments people post about the news articles they present come from individuals who are reacting to the headline and not the article itself [5]. In the case of Twitter, researchers examined 2.8 million online news articles that Twitter users shared, and to which they sometimes added their own original comments. More than half the time, according to computer records, a majority of people who shared the articles never clicked the link that would have enabled them to read the story. It’s clear that people are quite happy to share, retweet, or like things without ever having read them [6]. In terms of the spread and influence of fake news, this could be quite damaging. For example, the rise of clickbait relies on flashy headlines that draw attention [7]. If people only read the headlines, they may mistakenly take what is in the headlines as fact without exploring further whether there’s doubt or another side expressed in the story. Sharing without reading can also make stories look like they are gaining popularity, or trending [8]. This makes it more likely for other people to read or retweet them, also. It becomes a social cognitive epidemic.

Popularity Cues Affect Acceptance

Another bias has to do with how popular a news item appears to be. The well-known "bandwagon effect" takes place when it appears that a lot of other people like something, making us more likely to support it, too [9].

Source: agorapulse

In terms of fake news, the bandwagon effect occurs when we see how many times something has been shared or liked, rather than due to the content itself [10]. How many stars a story gets, or what percentage of people rated a story positively, affects belief, as well [11]. The popularity of something allows us to bypass assessing information. If thousands of other people have shared a piece of news, surely someone else has verified it, right? Unfortunately as we've already learned, shares and like can often come about without anyone reading what's being shared [6]. Moreover, bots—whose sole purpose is to make certain news stories look frequently read and recommended—can also inflate the apparent popularity of fake news items.

Popularity perceptions can influence not only our attention but also our behavior. Just as we seem to like what others like, we also want to be liked and present a good image of ourselves to others [12]. Research has verified that the desire to appear in-the-know is one reason many people give to explain why they’ve shared information that they haven't read [3]. A recent study found that, when people share a fake news story, the more likes they get for doing so, the more they believe the fake news they shared [13].

We also use other people’s comments as a guide for how to interpret online news, whether it’s true or false. Human psychological tendencies towards conformity with a group lead us to say what people we perceive to be like us are saying [14]. Comments posted to social media content also affect our evaluation of the content, and we often reflect the attitudes about the topic that the comments connote, especially when we identify with the commenters [15].

The Pernicious Impact of Partisanship

Source: BBC

A third type of bias comes from our existing political alignment, in the form of partisanship. When it comes to news and information generally, one’s identification as a Democrat or Republican, or one’s self-image of being liberal vs. conservative, has a big impact on what we readily believe or reject in the news, regardless of its truthfulness. As uncomfortable as this may be to accept, abundant research shows that people frequently reject news that’s inconsistent with their political ideology, and are prone to accept news that’s consonant with their political orientation.

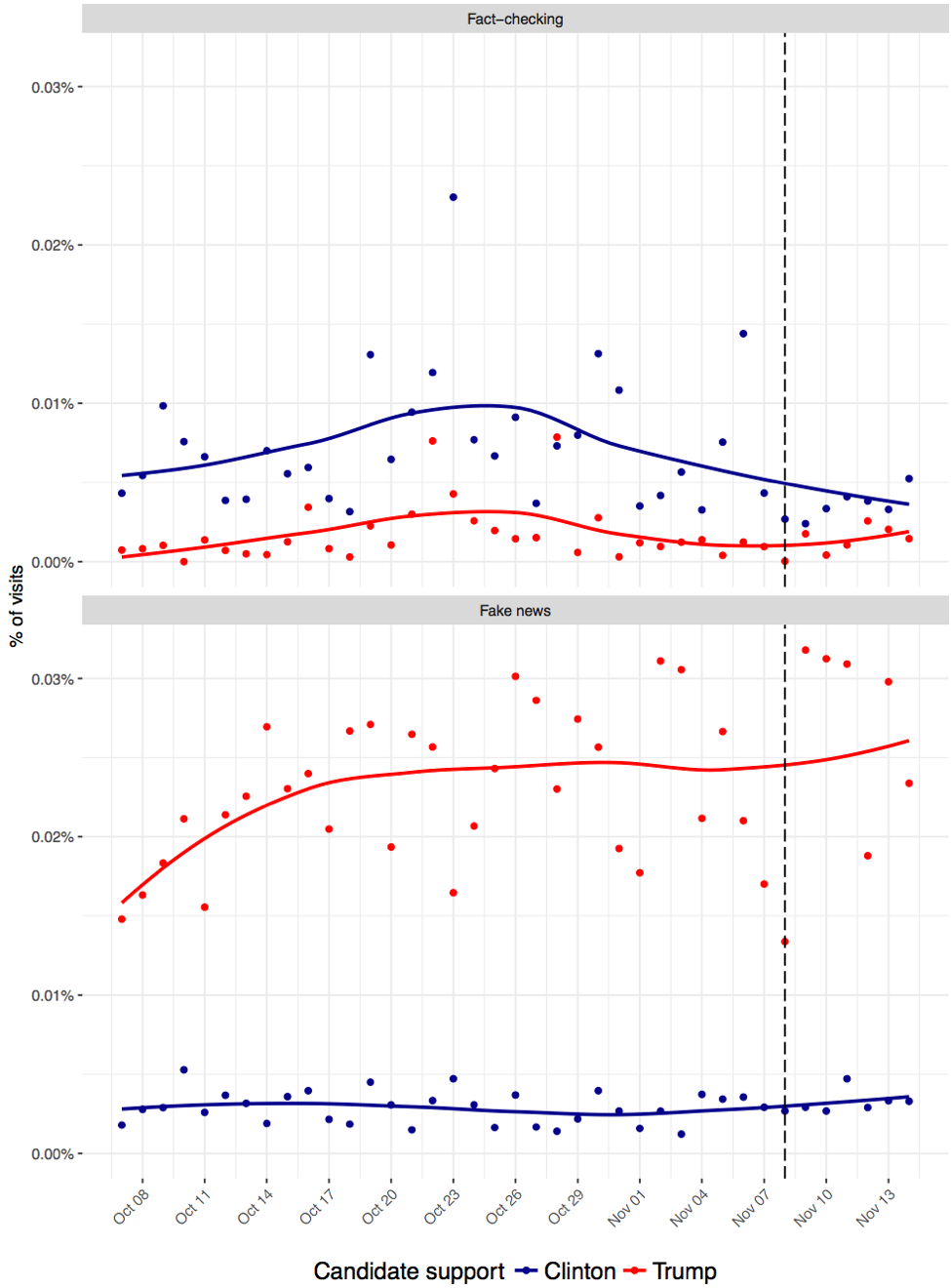

Like it or not, research demonstrated quite clearly that most politically-oriented fake news during the 2016 US election campaigns was consumed by conservatives, with Donald Trump supporters being especially likely to encounter and visit fake news sites [16]. As the table below indicates, on average, Hillary Clinton supporters were more likely to visit fact-checking websites and less likely to visit fake news websites. Trump supporters were less likely to visit fact-checking websites and more likely to visit fake news websites:

Source: Guess et al., 2018 [16]

We don't yet understand exactly why this was the case. Many private individuals who attempted to make money off of fake news, who had no political preference at all, claimed that they attempted to do so by manufacturing stories that would attract both conservatives and liberals. However, they abandoned the pro-liberal fake news specifically because liberals were not clicking on it [17]. Russian propagandists, in contrast, were more capable of spreading false or misleading advertisements that had either pro-liberal and pro-conservative messages. In any case, fake news, in the 2016 Presidential election was a significantly conservative phenomenon.

Source: Facebook Newsroom

Under pressure, social media platforms took many steps to slow the spread of fake news online. Facebook uncovered (and removed) numerous Russian-backed fake accounts in the summer of 2018, which had announced bogus events (like the “No Unite the Right 2”) in order to mobilize liberals, feminist groups, and minority members to stage counter-protests to unreal events. Whether things have gotten better isn’t clear. For instance, the public interest research group AVAAZ conducted an “analysis of the steps Facebook took throughout 2020 (and) shows that if the platform had acted earlier…it could have stopped 10.1 billion estimated views of… misinformation over the eight months before the (2020) US elections” [18].

The Persistence of Inaccuracy

One final way that cognitive biases can be troubling is in how long they can last and how they provide barriers to un-doing false beliefs. It would be nice if simply telling people when information they’re consuming is false would do the trick. Unfortunately, it isn’t so.

Researchers have found that our memory is quite poor when it comes to remembering what’s real and what isn’t, as long as we’ve seen something. In the case of fake news, Professor Emily Thorson at Boston College found that even in the face of information corrections, "belief echoes" often remain [19]. Belief echoes occur when people remember fake news and claim that it was true, even when they were later presented with correct information. Misinformation is notoriously sticky in people's heads, and simply correcting it in the form of another message can only go so far.

Even if there were to be some form of correction on fake news stories that would warn people to take them with a grain of salt, the absence of those warnings may have a greater impact than their presence. Gordon Pennycock and David Rand at Yale University examined if warning about fake news would affect people’s belief in information. While people were indeed less likely to believe stories that had a warning attached, when the warning wasn't present they were more likely to believe the stories, fake or not [20]. When people know that warnings are a possibility, they may feel as though they can let their guard down, and then if there is no warning, they think that the information is likely to be believable, which unfortunately may not be the case.

Other research, focusing on Twitter, has shown that users who post fact checks about a fake news story often post misleading content along with the fact check article, too, and what they write may actually contradict what the fact check indicates [6]. Even if people take the further step of examining the original source of a news item, insidious clickbait artists have been known to make the hosting site look as similar to a real news site as possible [7].

We have a lot more information about fact checking elsewhere on this site, but from the perspective of cognitive biases, it’s possible that the reason fact-check services aren't clicked much is simply because people don't think they need them. The most common way that people evaluate whether information is true or not is to use their own intuition [21]. People tend to feel more confident about their ability to identify something that isn’t true, than they really are [22]. Moreover, people also think that they themselves are less likely to be influenced by media messages than they think other people will be, an illusion commonly called a "third-person effect" [23]. Fact checkers don't have enough of an impact because we mistakenly assume we don't need them, even when we’re being fooled.

How Social Media Platforms Help Us Fall for Fake News

Social media platforms actually benefit commercially from fake news, since these sensationalized stories increase engagement on their sites, shares, and likes. Social media websites inherently support and expand the reach of misinformation through popularity indicators and the ability for bots to inflate the perceived credibility of posts through likes, comments, and shares. Social media platforms are the ideal “home” for fake news for several reasons [24]:

1. The cost of entry is low. It is practically “free” for sources of fake news content to enter social media platforms and post misinformation online.

2. The digital appearance and format of social media platforms make it challenging to determine the true source or credibility of news articles. Fake news sources often utilize similar website domain names as credible news outlets to trick users into believing that misinformation is coming from reputable sources. Take a look at an example of this strategy:

Source: Washington State University Libraries

This website imitates mainstream news sources by replicating the design of BBC.com and using a similar domain name to fool readers into thinking that this source is from the British Broadcasting Corporation. A quick glance at the URL would trick viewers as it begins with bbc.com, but notice that the full URL is bbc.com-latest-news.xyz. If this populated on your news feed, it would be difficult to identify this link as a fake news site.

3. Our networks on social media platforms tend to be ideologically homogenous, meaning that one’s Facebook friends or Instagram followers are likely to share similar beliefs as each of us do. We are most likely to read, share, and interact with news articles that align with our ideological positions, creating echo chambers and increasing the chances of sharing fake news.

Basically, social media platforms themselves and the ways they are designed help users “fall” for fake news. It is not 100% the users’ fault, but rather that platforms and users have a unique relationship that ultimately results in the spread of fake news online.

Other Reasons We Share Fake News Online

Social media users are motivated to share news online to engage in self-expression, socialization, build relationships, and gain social status. We share news online even if it may seem too salacious to be true, if we believe it may be interesting or entertaining to our social networks. We develop a sense of connection with our online communities by sharing news and information, addressing our need for social interaction.

[25]

Sometimes we intentionally share fake news in order to warn, educate, engage in collective fact-checking, and engage in humor or mockery [26]. Until quite recently, research has characterized those who spread fake news on social media as doing so reactively and reflexively, rather than proactively. Astute researchers have now begun to ask about the extent to which people share false stories specifically in order to warn other people about their falsity, to educate them, or encourage fact-checking.

References

[1] S. T. Fiske and S. E. Taylor, Social Cognition: From Brains to Culture, 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2013.

[2] D. Bennett, “What If Healthy People Don’t Want to Buy Obamacare?,” The Atlantic, Jun. 03, 2013. https://www.theatlantic.com/national/archive/2013/06/what-if-healthy-people-dont-want-buy-obamacare/314659/ (accessed Aug. 02, 2018).

[3] T. Hale, “Marijuana Contains ‘Alien DNA’ From Outside Of Our Solar System, NASA Confirms,” IFLScience, Jul. 13, 2013. www.iflscience.com/editors-blog/marijuana-contains-alien-dna-from-outside-of-our-solar-system-nasa-confirms/ (accessed Aug. 02, 2018).

[4] NPR.org, “Why Doesn’t America Read Anymore?,” NPR.org, Dec. 14, 2016. https://www.npr.org/2014/04/01/297690717/why-doesnt-america-read-anymore (accessed Aug. 02, 2018).

[5] M. Gabielkov, A. Ramachandran, A. Chaintreau, and A. Legout, “Social Clicks: What and Who Gets Read on Twitter?,” in Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGMETRICS International Conference on Measurement and Modeling of Computer Science, New York, NY, USA, 2016, pp. 179–192. https://doi.org/10.1145/2896377.2901462.

[6] C. Shao et al., “Anatomy of an Online Misinformation Network,” PLOS ONE, vol. 13, no. 4, p. e0196087, Apr. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196087.

[7] C. Silverman and L. Alexander, “How Teens In The Balkans Are Duping Trump Supporters With Fake News,” BuzzFeed News, Nov. 23, 2016. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/how-macedonia-became-a-global-hub-for-pro-trump-misinfo#.nfGBdzv3rN (accessed Aug. 02, 2018).

[8] G. King, J. Pan, and M. E. Roberts, “How the Chinese Government Fabricates Social Media Posts for Strategic Distraction, not Engaged Argument,” American Political Science Review, vol. 111, no. 3, pp. 484–501, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055417000144

[9] S. S. Sundar, S. Knobloch-Westerwick, and M. R. Hastall, “News Cues: Information Scent and Cognitive Heuristics,” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, vol. 58, no. 3, pp. 366–378, Feb. 2007, https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20511.

[10] M. J. Metzger and A. J. Flanagin, “Using Web 2.0 Technologies to Enhance Evidence-Based Medical Information,” Journal of Health Communication, vol. 16 Suppl 1, pp. 45–58, 2011, https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2011.589881.

[11] J. B. Walther, J. Jang, and A. A. H. Edwards, “Evaluating Health Advice in a Web 2.0 Environment: The Impact of Multiple User-Generated Factors on HIV Advice Perceptions,” Health Communication, vol. 33, no. 1, pp. 57–67, Jan. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1242036.

[12] C. A. Insko, R. H. Smith, M. D. Alicke, J. Wade, and S. Taylor, “Conformity and Group Size: The Concern with Being Right and the Concern with Being Liked,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, vol. 11, no. 1, pp. 41–50, 1985, https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167285111004.

[13] J. B. Walther, Z. Lew, J. Quick, and A. Edwards, “The Effect of Social Approval on Attitudes Toward the Focus of Fake News in Social Media,” presented at the Annual Meeting of the International Communication Association, Paris, May 2022.

[14] J. Colliander, “‘This is fake news’: Investigating the Role of Conformity to Other Users’ Views when Commenting On and Spreading Disinformation in Social Media,” Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 97, pp. 202–215, Aug. 2019, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.03.032.

[15] J. B. Walther, D. DeAndrea, J. Kim, and J. C. Anthony, “The Influence of Online Comments on Perceptions of Antimarijuana Public Service Announcements on YouTube,” Human Communication Research, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 469–492, 2010, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.2010.01384.x.

[16] A. Guess, B. Nyhan, and J. Reifler, “Selective Exposure to Misinformation: Evidence from the Consumption of Fake News During the 2016 U.S. Presidential Campaign,” Jan. 09, 2018. https://www.dartmouth.edu/~nyhan/fake-news-2016.pdf (accessed Aug. 03, 2018).

[17] L. Sydell, “We Tracked Down A Fake-News Creator In The Suburbs. Here’s What We Learned,” NPR.org, Nov. 23, 2016. https://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2016/11/23/503146770/npr-finds-the-head-of-a-covert-fake-news-operation-in-the-suburbs (accessed Aug. 02, 2018).

[18] AVAAZ, “Facebook: From Election to Insurrection,” AVAAZ, Mar. 18, 2021. https://secure.avaaz.org/campaign/en/facebook_election_insurrection/ (accessed Jun. 30, 2022).

[19] E. Thorson, “Belief Echoes: The Persistent Effects of Corrected Misinformation,” Political Communication, vol. 33, no. 3, pp. 460–480, Jul. 2016, https://doi.org/10.1080/10584609.2015.1102187.

[20] G. Pennycook and D. G. Rand, “The Implied Truth Effect: Attaching Warnings to a Subset of Fake News Stories Increases Perceived Accuracy of Stories Without Warnings,” Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY, SSRN Scholarly Paper ID 3035384, Dec. 2017. Accessed: Aug. 02, 2018. [Online]. Available: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3035384

[21] E. C. Tandoc, R. Ling, O. Westlund, A. Duffy, D. Goh, and L. Zheng Wei, “Audiences’ Acts of Authentication in the Age of Fake News: A Conceptual Framework,” New Media & Society, vol. 20, no. 8, pp. 2745–2763, Aug. 2018, https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444817731756.

[22] M. Metzger, A. Flanagin, and E. Nekmat, “Comparative Optimism in Online Credibility Evaluation Among Parents and Children,” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, vol. 59, no. 3, pp. 509–529, Jul. 2015, https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2015.1054995.

[23] A. C. Gunther and J. D. Storey, “The Influence of Presumed Influence,” Journal of Communication, vol. 53, no. 2, pp. 199–215, Jun. 2003, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.2003.tb02586.x.

[24] H. Allcott and M. Gentzkow, “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 211–236, May 2017, https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.31.2.211.

[25] A. Duffy, E. Tandoc, and R. Ling, “Too Good to be True, Too Good Not to Share: The Social Utility of Fake News,” Information, Communication & Society, vol. 23, no. 13, pp. 1965–1979, Nov. 2020, https://doi.org/10.1080/1369118X.2019.1623904.

[26] M. J. Metzger, A. J. Flanagin, P. Mena, S. Jiang, and C. Wilson, “From Dark to Light: The Many Shades of Sharing Misinformation Online,” Media and Communication, vol. 9, no. 1, Art. no. 1, Feb. 2021, https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v9i1.3409.