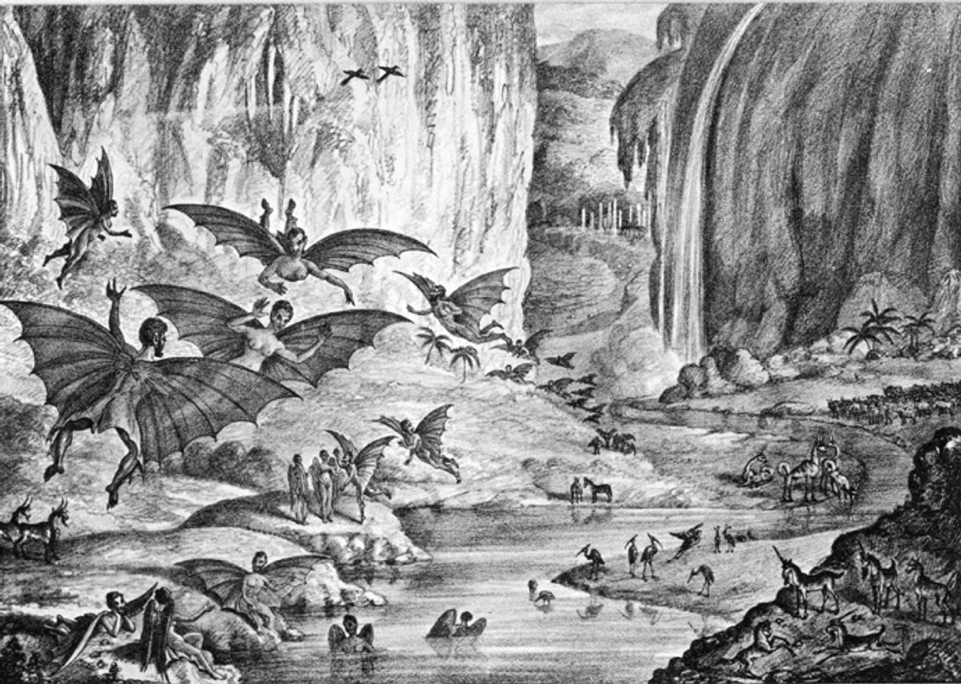

“Sensationalism always sold well. By the early 19th century, modern newspapers came on the scene, touting scoops and exposés, but also fake stories to increase circulation. The New York Sun’s 'Great Moon Hoax' of 1835 claimed that there was an alien civilization on the moon, and established the Sun as a leading, profitable newspaper.” [1]

The Great Moon Hoax by the tabloid The Sun from 1835. Depiction of moon surface. Source: Wikipedia

False and distorted news material isn’t exactly a new thing. It’s been a part of media history long before social media, since the invention of the printing press. It’s what sells tabloids. On the internet, headline forms called clickbait entice people to click to read more, by trying to shock and amaze us. What’s more outrageous to read about than fake things that didn’t actually happen?

History

There’s lots of examples of false news throughout history. It played a role in catalyzing the Enlightenment, when the Catholic Church’s false explanation of the 1755 Lisbon Earthquake prompted Voltaire to speak out against religious dominance. The very first American colonial newspaper ran a fake story about France’s Louis XIV [2]. In the 1800s in the US, racist sentiment led to the publication of false stories about African Americans’ supposed deficiencies and crimes. It was used by Nazi propaganda machines to build anti-Semitic fervor.

In the 1890s, rival American newspaper publishers Joseph Pulitzer and William Hearst competed over the audience through sensationalism and reporting rumors as though they were facts, a practice that became known at the time as “yellow journalism.” Their incredulous news played a role in leading the US into the Spanish-American War of 1898. Eventually there was a backlash against the lack of journalistic integrity: The public demanded more objective and reliable news sources, which created a niche that the The New York Times was established to fill at the turn of the 20th century. Yellow journalism became less common. That is, until the rise of web-based news brought it all back in full force.

One of the motivations for 1890s newspapers engaging in yellow journalism is the same as for fake news creators today: Exaggerated news with shocking headlines gets attention and sells papers (or prompts mouse-clicks), promoting the sale of advertising. In the form of traditional news media, most people have learned better than to take outrageous news articles as seriously as they did at the height of the yellow journalism era. More recently, tabloids like The National Enquirer and The New York Sun, and fad magazines like The Freak and The Wet Dog are generally known as false news sources. Similarly, people recognize that the parody news productions on the web and TV feature satire and ironic, but unreal, accounts of current events.

Source: Google Image Search

But that clarity simply isn’t available when news stories appear out-of-context via social media.

Of course, fake news is also used as a term to discredit news stories that individuals (particularly former president Donald Trump) don’t like, in order to suggest that they were made up or that they blow out of proportion something that should be trivial (even if other sources can verify their accuracy). In a conversation with Fox Business in October, 2017, Donald Trump claimed that he had "really started this whole 'fake news' thing." (Ironically, Hillary Clinton used the term in a speech two days before Trump’s first use of the phrase [3].)

Although Donald Trump may have appropriated the term in a whole new way, the term itself has been in use for many years. The first documented uses of the term occurred in the 1890s, according to Merriam Webster [4].

How Contemporary Fake News Is Different

No matter who started the “fake news thing,” fake news in its modern form is different from the historical forms of journalistic nonsense in traditional media outlets. The speed at which it is spread and the magnitude of its influence places it in a different category from its historical cousins. There are three unique parts to modern fake news that make it different from older varieties of intentionally exaggerated or false reporting: the who, the what, and the how.

Who

Fake news is created and spread by either those with ideological interests, such as Russian agents, or computer-savvy individuals looking to make some money, like Macedonian teenagers and certain suburban Americans. It’s not the newspaper publishers this time.

What

Source and video: BBC News

It often involves knowing distortion and deception of the news source, not just the content. In one tragic example, a video that was originally part of a public service announcement to help people be vigilant against child abduction in Pakistan, “was edited to look like a real kidnapping… (and) went viral,” leading to deadly attacks on innocent people suspected of kidnapping [5].

Here's another example of a fake news website:

This site attempts to imitate a mainstream news source by replicating the design of the BBC’s logo and by using a similar domain name (starting with bbc.com) to fool readers into thinking that this source is the British Broadcasting Service, or BBC. A quick glance at the URL would trick viewers as it begins with bbc.com, but notice that the full URL is bbc.com-latest-news.xyz. If this appeared on your news feed, it might be difficult to notice that this is a fake news site.

How

Three characteristics of social media’s presentation of news make people more likely to fall for fake news.

First, social media act as news aggregators that are "source-agnostic." That is, they collect and present news stories from a wide variety of outlets, regardless of the quality, reliability, or political leanings of the original source. Without a sense of the reputation of the original publisher being clear, it’s easy for fly-by-night provocateurs and manipulators to get their fake stories to approach the prominence of the traditional media outlets. If readers can’t readily identify who wrote or provided information for a story, it’s hard to judge its honesty without elaborate fact-checking, which most people don’t do.

Second, many news stories get conveyed to people on social media via their friends or people they follow, along with their implicit or explicit endorsement of the story such as a share, like, or retweet. These tacit recommendations make people more accepting of the messages they get. On social media apps, “Many messages are shared in groups, and when they are forwarded, there is no indication of their origin. (False stories) have often appeared to come from family and friends.”

Third, relatedly, social media platforms automatically tag articles with indications of their popularity (the number of views or likes they’ve gotten, which is further complicated by online robots that can systematically inflate popularity indicators), which also makes people more likely to tune in to a story when those counts are high.

All three of these characteristics work together to increase the chances that social media users share fake news. As news articles are shared within our online networks, they are stripped of critical context such as its original author or source, intention, or goal. Once an article reaches your news feed, it may have little resemblance to its original form. When this important context is lost, fake news articles are more likely to be shared amongst social networks [6].

So, while history offers some important lessons, this isn’t your grandparents’ fake news any more.

References

[1] J. Soll, “The Long and Brutal History of Fake News,” POLITICO Magazine, Dec. 18, 2016. http://politi.co/2FaV5W9 (accessed Aug. 02, 2018).

[2] Yeoman, “‘That’s Fake News!,’” The Saturday Evening Post, Jul. 06, 2022. https://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2022/07/thats-fake-news/ (accessed Jul. 06, 2022).

[3] M. Wendling, “The (Almost) Complete History of ‘Fake News,’” BBC News, Jan. 22, 2018. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/blogs-trending-42724320 (accessed Aug. 02, 2018).

[4] Merriam-Webster, “The Real Story of ‘Fake News,’” Mar. 23, 2017. https://www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/the-real-story-of-fake-news (accessed Aug. 02, 2018).

[5] V. Goel, S. Raj, and P. Ravichandran, “How WhatsApp Leads Mobs to Murder in India,” The New York Times, Jul. 18, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2018/07/18/technology/whatsapp-india-killings.html (accessed Aug. 06, 2018).

[6] A. J. Flanagin, “Online Social Influence and the Convergence of Mass and Interpersonal Communication,” Human Communication Research, vol. 43, no. 4, pp. 450–463, 2017, https://doi.org/10.1111/hcre.12116.