While the presence of fake news is not new, the internet and social media changed the ways it’s created and spread. Fake news is a multi-step process that involves making or taking content that others have produced, passing it off as real news, and capitalizing on social media to get as much attention as possible. This section explains how purveyors of fake news operate, and how fake news is created. It provides a step-by-step guide to how fake news producers utilize the internet and social media.

Fundamentally, those who operate fake news websites want as many visitors to their sites as possible. While some may want their visitors to see the content and have it influence their political values, others simply want internet users to click on them, which often takes users to a website where users see more content (ideological or not) and/or see advertising. When a website has ads on it, those visits pay the website owner advertising revenue. Both of these motivations—ideological and commercial—need as many people to click on the website link and visit as possible [1]. With this in mind, let’s go through the steps that go into creating a fake news factory.

Step 1: Creating a Fake News Site

The first step to creating a fake news factory is creating a website on which the fake news stories will be presented, or hosted. This requires two things, a domain name for the website and the host of the website itself. Each of these can be bought relatively cheaply, and both can be designed to look as much like legitimate news sites as possible [2].

The domain name for a website is an address that acts as the path your web browser takes to get to a particular place on the internet. A domain name typically looks something like www.example.com, and can be thought of as the website’s name. Domain names are registered, and every domain name is unique. Some popular website providers sell domain names for as little as $1 a year.

A webhost is the file space where the website itself is stored [3]. If a domain name is the address, the hosting service is the building at the address. The webhost is where the website code and files are held. This is slightly more expensive, but some cheaper hosting services offer web hosting for as little as $2.75 per month.

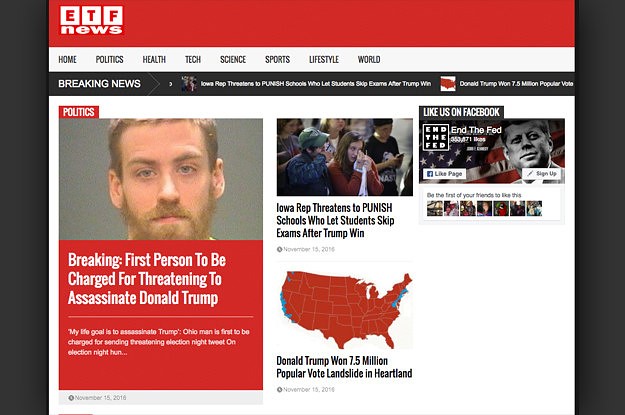

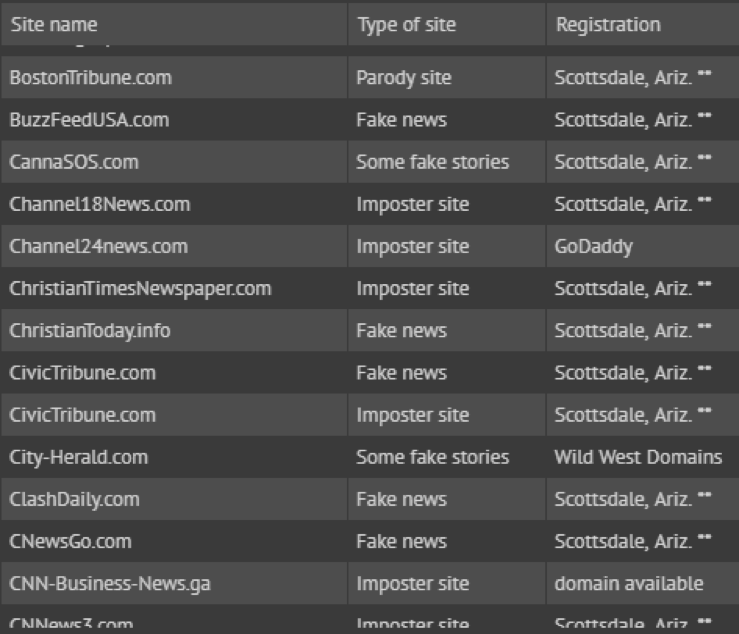

Now, the owners of fake news sites want them to look as much like a real news website as possible, so that people are more likely to trust them. Think about some examples of real news websites, like www.npr.org or www.nytimes.com. You’re likely to believe these are legitimate news sites because they look like the real news organizations you already know about. But what about sites like “www.abcnews.com.co” or “BostonTribune.com"? It’s less clear that these aren’t legitimate news sites, because their domain names alone might seem familiar. In fact, these used to be actual fake news sites. This is the strategy that most creators of fake news use in order to get people to visit and to think these sites are legitimate [2]. Politifact.com, working with Facebook, created a list you can look at of 330 fake news websites. Here’s a sample:

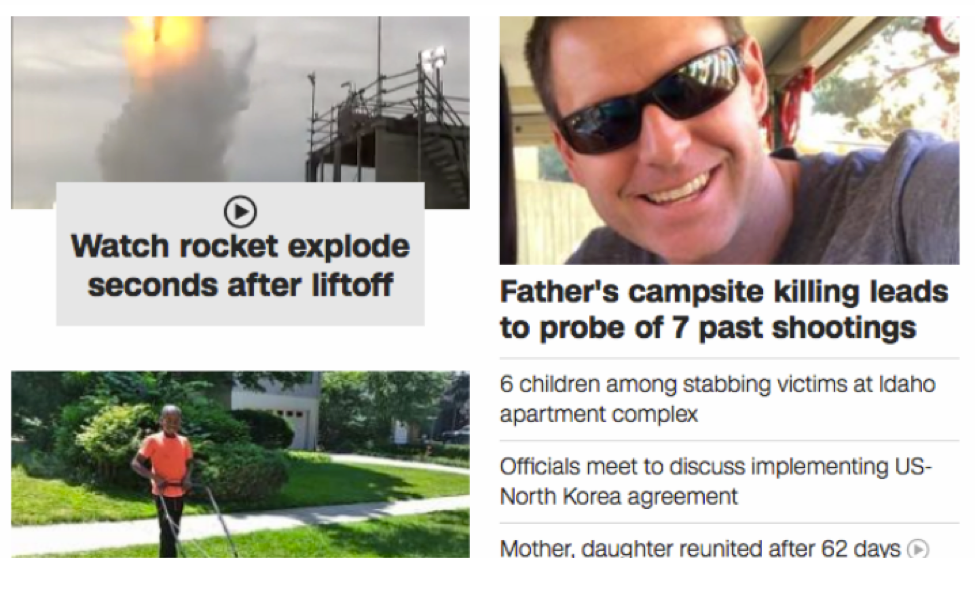

The strategy for creating a legitimate-looking domain address extends to how the website is supposed to look, too. The layout and design of fake news websites are purposely designed to look as much like real news sites as possible. Below are a few examples of fake news websites and real news websites. See if you can tell the difference between them.

The images above show the lengths that fake news providers go to in order to make their sites look as similar to mainstream online news sites as possible. The top four are all fake news sites, while the bottom two come from CNN and The New York Times.

Why do fake news websites do this? They want as much attention as possible. Think about the limited amount of time and interest you can dedicate to reading or watching news, or how often you click on something that you see on social media. You’re more likely to click on something you think is real than to waste time on something that’s obviously fake. Those who own these fake news sites know this, and resort to these sneaky methods to get your attention.

Step 2: Stealing Content

Now that our fake news factory has a sneaky domain name and a slick design, we need content for it. It’s possible that the owners of a fake news site could create their own content and try to pass it off as real. This is what many of the Russians did before and after the 2016 US elections, according to US Intelligence reports [4]. The downside to this is that this takes time and energy, and many fake news site owners want this process to be as simple and cheap as possible. So, fake news website owners often steal their content [5].

The most common place that fake news site owners steal from is satire websites or from sensationalistic “clickbait.” Satire websites like The Onion or Clickhole often post outrageous news parodies, and those who visit these satire sites know not to believe them. Clickbait news stories are like tabloids, with sensationalistic and dramatic headlines that entice readers to click to read more, even if the real stories are somewhat boring. Buzzfeed and Upworthy entice readers with these kinds of headlines, and fake news sites often steal content from them.

Fake news site owners will go to these websites, copy, and re-post the content on their own sites, attempting to pass this information off as factual. This process is easy, requiring only to copy and paste, with maybe a little reformatting, usually to the headline. The headline is most important and explosive headlines can make people click on a fake news story without even looking at who shared it or where it originated [6].

Step 3: Selling Advertising

Once our fake news factory has content, our next step is to monetize it. One motivation for fake news site owners is earning money from these websites. Advertising is the process through which they do this. The owners of these sites can make a small amount of money for each visitor to one of their webpages, and a slightly larger amount every time a visitor clicks on an advertisement on the page [7].

To the owners of these fake news sites, the process is largely automatic. The amount of control they have over the advertisements that appear on their sites is minimal but so is the work required to set them up. Owners of fake news websites sell parts of their website pages to advertising companies. The advertisers then run ads on these pages. The advertising companies act as the “middle-man” linking up ads bought by other companies to news sites, with the ad company’s algorithm deciding who sees what ads [8].

The algorithms developed by these ad companies use tracking data that websites collect based on a user’s web viewing history. By attaching cookies (tracking software) to your web browser they can note what other web pages you viewed and what you clicked on. Using these data, advertising companies can build a consumer profile that allows them to target the ads that are most likely to get you, or at least people like you, to click on them [9].

Fake news website owners only have to be concerned with getting as many people to visit their website as possible, while advertisers are concerned with having access to sections of the most popular websites to target their ads to as many people as possible. Our fake news website can now have more money coming in than the small amount of money initially invested in setting up.

Step 4: Spreading Via Social Media

Finally, fake news sites need visitors, and social media platforms provide them. Social media platforms inherently benefit from fake news because shocking, sensationalizing, and popular posts keep users engaged. Anything sensational draws readers in, and things that are untrue tend to be sensational [10]. For example, in relation to the 2016 Presidential election, research has shown that the most common route to fake news websites was through Facebook [11]. In other words, people see a headline or an abbreviated news story on Facebook, click on it (and the website address it points to), and their web browser opens to the specific page where the fake story is hosted. Thus, fake news site owners try to get as many clicks as possible via social media. The most common way of doing this are creating fake Facebook accounts, and posting fake news articles to Facebook groups and directing users to their website.

Fake social media accounts give fake news articles perceived credibility by inflating the popularity indicators they accrue. Popularity Indicators on social media platforms are likes, comments, shares, retweets—anything that reveals how many people saw or interacted with a particular piece of content. These indicators give fake news articles a false appearance of being credible, increasing the likelihood of more people interacting with and sharing false information [12]. The more likes, shares, and comments a post has, the more likely these posts will be populated onto your social media feed, since social media platforms use algorithms to determine the content that appears on each users' feed, and the algorithms are heavily influenced by the popularity of posts. Content with increasing numbers of likes, comments, and shares are more likely to appear on a user’s feed [13].

Like the way fake news site operators steal content and pass it off as real, they can steal identities, make fake accounts on social media platforms, and pass those off as real, too [14]. The accounts look as though they belong to ordinary people, often from small towns in the U.S., but with pictures and names stolen from other users. They look like ordinary citizens that have no intent to manipulate others.

These fake personae, however, don’t come with their own friends or followers from real life, that their fake news can spread to. One blanket strategy to overcome this is to add friends at random and send them links to the fake news site. A more targeted strategy involves finding existing interest groups on Facebook, or hashtags on Twitter, with exploitable interests. For example, one could send outrageous headlines (and links) about cat abuse to social media groups of cat lovers. Or if a fake news website is loaded with anti-vaccine content and COVID-19 conspiracy theories, an easy way to get clicks would be to post headlines and links to Facebook groups that are anti-vaxx or COVID-conspiracists themselves. This type of social media seeding is the most proactive and efficient step to promote our fake news factory.

Step 5: Repeat

The more fake news sites that owners have, the more advertising they can get paid for displaying, but the more clicks they need as well. Attention is generally concentrated on only a few fake news sites, with many more receiving almost no attention at all [15]. Therefore, in order to create a successful fake news factory, there’s often a lot of trial and error. Some websites get a lot of traffic, some get none. Alternatively, some copyright complaints may take down fake news sites, in which case the owners shut down the first site, only to start another using the same process.

The fake news factory model is so successful because it can be easily replicated, streamlined, and requires very little expertise to operate. Clicks and attention are all that matter, provided you can get the right domain name, hosting service, stolen content, and social media spread.

References

[1] L. Sydell, “We Tracked Down A Fake-News Creator In The Suburbs. Here’s What We Learned,” NPR.org. https://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2016/11/23/503146770/npr-finds-the-head-of-a-covert-fake-news-operation-in-the-suburbs (accessed Aug. 02, 2018).

[2] C. Silverman and L. Alexander, “How Teens In The Balkans Are Duping Trump Supporters With Fake News,” BuzzFeed News, Nov. 23, 2016. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/craigsilverman/how-macedonia-became-a-global-hub-for-pro-trump-misinfo#.nfGBdzv3rN (accessed Aug. 02, 2018).

[3] WebHostingGeeks.com, “Beginner’s Guide to Domain Names,” WebHostingGeeks.com. https://webhostinggeeks.com/guides/domains/ (accessed Aug. 02, 2018).

[4] Office of the Director of National Intelligence, “Assessing Russian Activities and Intentions in Recent US Elections,” Jan. 06, 2017. https://www.dni.gov/files/documents/ICA_2017_01.pdf (accessed Aug. 03, 2018).

[5] NPR.org, “Fake News Expert On How False Stories Spread And Why People Believe Them,” NPR.org, Dec. 14, 2016. https://www.npr.org/2016/12/14/505547295/fake-news-expert-on-how-false-stories-spread-and-why-people-believe-them (accessed Aug. 03, 2018).

[6] M. Gabielkov, A. Ramachandran, A. Chaintreau, and A. Legout, “Social Clicks: What and Who Gets Read on Twitter?” in Proceedings of the 2016 ACM SIGMETRICS International Conference on Measurement and Modeling of Computer Science, New York, NY, 2016, pp. 179–192. https://10.1145/2896377.2901462.

[7] BBC News, “How Do Fake News Sites Make Money?,” BBC News, Feb. 09, 2017. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/av/business-38919403/how-do-fake-news-sites-make-money (accessed Aug. 03, 2018).

[8] J. Albright, “#Election2016: Propaganda-lytics & Weaponized Shadow Trackers,” Medium, Nov. 22, 2016. https://medium.com/@d1gi/election2016-propaganda-lytics-weaponized-shadow-trackers-a6c9281f5ef9 (accessed Aug. 02, 2018).

[9] E. Sutton, “Trump Knows You Better Than You Know Yourself,” aNtiDoTe Zine, Jan. 22, 2017. https://antidotezine.com/2017/01/22/trump-knows-you/ (accessed Aug. 02, 2018).

[10] K. D. Coduto and J. Anderson, “Cognitive Preoccupation with Breaking News and Compulsive Social Media Use: Relationships with Online Engagement and Motivations for Use,” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, vol. 65, no. 3, pp. 321–335, May 2021, https://10.1080/08838151.2021.1972114.

[11] A. Guess, B. Nyhan, and J. Reifler, “Selective Exposure to Misinformation: Evidence from the Consumption of Fake News During the 2016 U.S. Presidential Campaign,” Jan. 09, 2018. https://www.dartmouth.edu/~nyhan/fake-news-2016.pdf (accessed Aug. 03, 2018).

[12] E. Thorson, “Changing Patterns of News Consumption and Participation,” Information, Communication & Society, vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 473–489, Jun. 2008, https://10.1080/13691180801999027.

[13] D. M. J. Lazer et al., “The Science of Fake News,” Science, vol. 359, no. 6380, pp. 1094–1096, 2018, https://10.1126/science.aao2998.

[14] S. Shane, “The Fake Americans Russia Created to Influence the Election,” The New York Times, Jan. 20, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/07/us/politics/russia-facebook-twitter-election.html (accessed Aug. 02, 2018).

[15] S. Vosoughi, D. Roy, and S. Aral, “The Spread of True and False News Online,” Science, vol. 359, no. 6380, pp. 1146–1151, Mar. 2018, https://10.1126/science.aap9559.