The term fake news means “news articles that are intentionally and verifiably false” [1] designed to manipulate people’s perceptions of real facts, events, and statements. It’s about information presented as news that is known by its promoter to be false based on facts that are demonstrably incorrect, or statements or events that verifiably did not happen.

Fake news “is fabricated information that mimics news media content in form but…lack(s) the news media’s editorial norms and processes for ensuring the accuracy and credibility of information” [2]. It overlaps with misinformation (false or misleading information) and disinformation (false information purposely spread to mislead people).

The definition may seem a bit vague, but it’s important. People have used the term “fake news” to mean different things.

A 1.5 minute BBC News video describes different meanings of "fake news"

This definition eliminates unintentional reporting mistakes, rumors that don’t originate from a news article, suspicions/interpretations/conspiracy theories, satire, and biased (but not false) reports.

It also leaves out sweeping indictments of mainstream media. Former president Donald Trump had his own definition for fake news, labelling “fake news” as the reporting of uncomplimentary things that seemed distracting or insignificant, and especially reports that portrayed him in a negative light instead of highlighting successes that he thought should have been made more prominent.

This site isn’t about that.

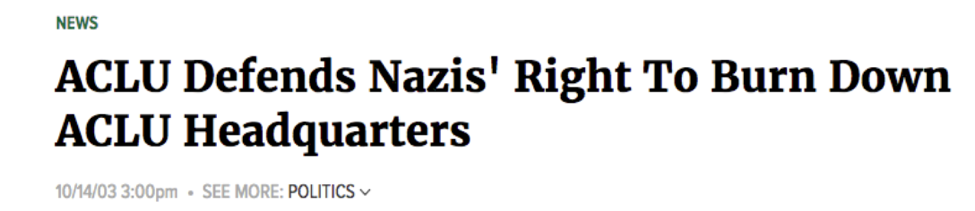

With this definition, works of satire like The Onion (see below) or The Daily Show aren’t trying to deceive, and can’t be construed as fake news, although people might mistakenly assume their content to be true.

Source: The Onion (a satirical online news magazine)

Oddly enough, these satirical stories can turn into fake news when the same story is re-published on a different site that tries to make it appear as factual reporting [3]. Like this one, that started as a parody, but went viral when presented as if it was actual:

(Governor Palin never said this.)

Fake news in social media has become a real problem in politics, but it’s older and it’s broader.

Clickbait

“Clickbait” refers to a headline or the leading words of a social media post (the teaser message) written to attract attention and encourage visitors to click a target link to a longer story on a web page [4]. Clickbait offers odd, amazing, or suspenseful phrases that induce curiosity, and entice people to want to know more. Like this:

Source: Medium.com

They don’t need pictures to be clickbait. For example,

- A Man Falls Down And Cries For Help Twice. The Second Time, My Jaw Drops

- 9 Out Of 10 Americans Are Completely Wrong About This Mind-Blowing Fact

- Here’s What Actually Reduces Gun Violence [5]

Clickbait is a common way that fake news (and any kind of content) is spread. Clickbait depends on creating a “curiosity gap,” an online cliffhanger of sorts that poses headlines that pique your curiosity and lead you to click the link and read on. The gap between what we know and what we want to know compels us to click. To an extent, the more outrageous a teaser message is, the more successful clickbait may be.

Besides curiosity and outrage, clickbait often uses a number of language characteristics that draw people in. Many clickbait headlines offer a list of some kind – these 10 things that will blow your mind about… — and the titles have a number in them (and usually start with it) [6]. According to a review by Martin Potthast and colleagues [4], clickbait teasers contain strong nouns and adjectives, but use simple, easily readable language. They use these and this a lot.

You see these attention-getting strategies in conventional tabloids, too, like the National Enquirer. They’re the kind of goofy leads that The Onion likes to parody.

Clickbait motivates further reading, instantly, and further reading promotes advertising for website publishers, so it’s a widespread practice. Fake news headlines often look this way, just as they did in the fake news peddled by tabloids and the era of yellow journalism.

References

[1] H. Allcott and M. Gentzkow, “Social Media and Fake News in the 2016 Election,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 31, no. 2, pp. 211–236, May 2017, https://10.1257/jep.31.2.211

[2] D. M. J. Lazer et al., “The Science of Fake News,” Science, vol. 359, no. 6380, pp. 1094–1096, Mar. 2018, https://10.1126/science.aao2998

[3] E. C. Tandoc, Z. W. Lim, and R. Ling, “Defining ‘Fake News’: A Typology of Scholarly Definitions,” Digital Journalism, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 137–153, Feb. 2018, https://10.1080/21670811.2017.1360143

[4] M. Potthast, S. Kopsel, B. Stein, and M. Hagen, “Clickbait Detection,” in Advances in Information Retrieval: 38th European Conference on IR Research, ECIR 2016, Switzerland: Springer, 2016, pp. 810–817.

[5] Y. Chen, N. J. Conroy, and V. L. Rubin, “Misleading Online Content: Recognizing Clickbait as False News,” 2015. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?doid=2823465.2823467 (accessed Aug. 03, 2018).

[6] B. Vijgen, “The Listsicle: An Exploring Research on an Interesting Shareable New Media Phenomenon,” Studia UBB Ephemerides, vol. 59, no. 1, pp. 103–122, Jun. 2014, [Online]. Available: http://studia.ubbcluj.ro/download/pdf/894.pdf